In case you missed it, it’s election season. While the campaign process doesn’t immediately conjure up ideas of introspection, thoughtful exchanges of ideas, and learning that facilitators typically support, there are still good lessons to be learned this fall… even from the presidential debates.

Facilitator/Moderators and Evaluation of Truth

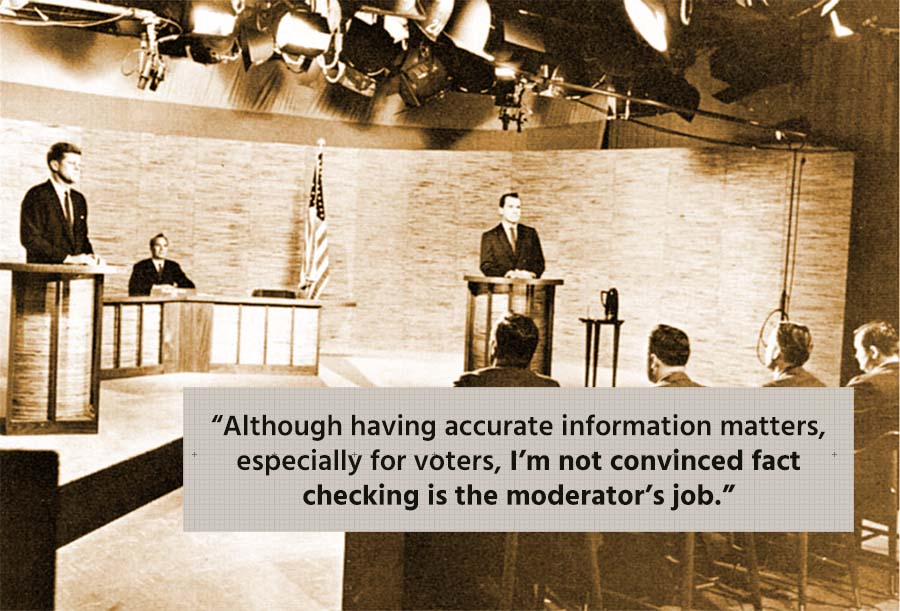

Before the first debate, everyone was in a tizzy about whether and how Lester Holt would serve as a fact-checker for the candidates’ claims. Although having accurate information matters, especially for voters, I’m not convinced fact checking is the moderator’s job.

As a facilitator, it’s my role to expand and deepen people’s understanding and to establish and protect “the space” for the group to do its best work. Debating the relative validity of statements often misses the point and a facilitator correcting one side or the other could compromise the space and derail the entire group. In reality, the fact that someone sees something as true, whether or not others agree or validate that truth, is information in itself. Instead of fact-checking in the face of unexpected information, a facilitator might ask “Can you tell us a little more about how you came to those conclusions?” or “Interesting point, I wonder if there are other perspectives that we might consider as a group?” In this case, it’s up to the group to do the exploring together and, when necessary, add other perspectives to the conversation.

Facilitator/Moderators and Intervention

Following the vice-presidential debate and the second presidential debate, much has been made of the ways that the moderators intervene in candidates’ responses. While Lester Holt largely sat back and let the candidates go subsequent moderators were more assertive. The vice-presidential moderator Elaine Quijano repeatedly tried to corral her candidates’ cross talking and question dodging. Similarly, Anderson Cooper and Martha Raddatz intervened to focus the candidates’ responses on the actual questions. These interventions prompted many to proclaim that Martha Raddatz was the real winner of the second debate while others complained she was overzealous. Which of these approaches best serves the needs of the voters? Which best aligns with the philosophical foundations of our democracy? Which do you prefer in your own facilitation practice?

The challenging of knowing when to intervene and when to sit back is SO real. I love Meg Bolger’s Stop Talking and Trust the Group video.

As an extrovert who gets really excited and jumps in like a participant, Meg’s ideas totally resonate with me! It’s definitely worth doing a gut-check before intervening to make sure you’re jumping in to support the process, not to contribute content. Even if we just focus on whether and how to intervene in the process, it’s still hard to know when to jump in and when to wait, when to let the group do the work.

In evaluating potential facilitator intervention, context matters. What’s the purpose of the group? What processes and structures will best support those outcomes?

Politicians are notorious about telling the story they want to tell, regardless of what question was posed of them. Done with skill, these pivots from the question to an entirely different answer go unnoticed. Done poorly, it’s clear that they’re dodging the question. Regardless, if the candidates aren’t answering the question, the public isn’t learning. If it’s a facilitator’s job to help the group (voters?) do their best thinking together, it seems that thoughtful intervention to re-focus a candidate on the actual question is important. If I pose a question to draw out important information, and the group doesn’t actual get that information, the facilitator in me would feel justified in jumping in and asking the question again.

If we think intervention is appropriate, it’s worth considering ways of doing this that continue to hold the space for all participants. What are ways that you have seen this done effectively? Is it appropriate to interrupt a wandering answer for the sake or time or better to let the person finish and then re-pose a question? What’s your style when intervening and how does this style impact your groups? This leads into the final facilitator/moderator consideration: neutrality.

Facilitator/Moderators and Neutrality

Countless trainings for mediators and facilitators explore the challenge/myth of neutrality, and with good reason; neutrality is complicated and difficult! Across contexts, people want to feel like they’ve had a fair chance to be heard, that their ideas are treated with respect, and that outcomes reflect the will of the group, not the biases of the facilitator. In an election context, neutrality (of moderators and indeed of the entire voting process) is both critically important and potentially difficult to achieve. In the case of the presidential debates, a bipartisan commission comes together to negotiate all kinds of details, especially the selection of moderators. Even with this careful vetting, minor actions from the moderators can be blown into major claims of bias. This begs the question: How do you know when a facilitator or moderator is biased?

Admittedly, different people receive different treatment in a facilitated process. To keep balance, a facilitator may ignore an outspoken participant and specifically encourage a quieter one. They may ask participants to write down ideas instead of sharing ideas vocally (privileging particular styles over others). These approaches may be maddening to the outspoken participant who wants to talk more but are also clearly a help to the group in doing its best work together. Thinking back to the idea of intervention, if one person wanders further from the group’s focus, that person will need more active intervention, even full correcting, to stay on track. This individual may feel singled out and like the facilitator or moderator is treating them unfairly.

When evaluating potential bias, it’s again worth remembering context. If the goal is to keep participation balanced and to focus on the group’s identified areas of interest, different treatment of participants seems both necessary and desirable. We all know the Rolling Stones’ view on this. I would even go so far as to say, “…you just might find, you get what the GROUP needs!” Interestingly, even when different treatment of participants aligns with the group’s goals, perceived bias can still be incredibly destructive. As a facilitator, I again wonder what words, tone of voice, and dispositions can intervene for the good of the group and its goals without alienating any one participant.

Thinking with my social justice hat on, I also want to call out that neutrality itself isn’t always best. If we are to address power imbalances and stop destructive behavior, it’s not enough for facilitators to sit idly by in the name of being neutral. If one participant’s behavior violates the group’s norms or otherwise impedes a safe and thoughtful exchange of information, a facilitator is wise to intervene. Again, depending on how this happens, the above intervention may be seen as vitally important or biased and destructive. When I think about the overarching goals of my work, I again wonder how I can best call someone “in” when I call out behaviors that are hurting the group. A look at “neutrality” in the face of destructive behaviors (both for the moderators in the debates and the press as a whole) from this election season could be a whole book on its own.

Needs of the Group

As we come into the final weeks of this election, I’d be remiss to not mention the role of the rest of us, the “group,” the voting public who will ultimately make decisions that will impact our future. While groups need strong facilitators/moderators to do their best work together, it’s also up to the group members themselves to shape the reality they hope to see. For all the attention that gets put on the candidates, the debate moderators, the polls, and the media, each election it’s worth considering the ways that we as the voting public are helping reach the outcomes we desire.

When I think about “outcomes” in this context, I’m not talking about the election results that will be broadcast the night of November 8. This isn’t a plea to jump on anyone’s campaign wagon. Instead, I think about outcomes in terms of the kind of country we want to live in and our visions for the ways we can live and work in diverse communities. I think about the ways that we can model and support those outcomes, the ones that matter far more than who wins on election night.

I hope that at some point, as a “group” we’ll take a collective break from arguing over who’s right or wrong and listen to one another. I hope that we will call on our best, most curious, most open-minded, most patient selves and reach out to those whose life experiences (and political views) are different from our own. I hope that as facilitators, we can both nurture these opportunities for others AND engage with themselves ourselves.

This article was written by Carrie Bennett and has been modified from it’s original version. You can find the original post here. Carrie is a facilitator, mediator, and trainer for Learning Through Difference, LLC. She loves helping groups get to the heart of issues that matter with safety and efficiency. Beyond work, she has a healthy obsession with backyard chickens, roller skates, and her freshwater shrimp Conrad. She lives in Northern Colorado with frequent visits to the Pacific Northwest.

This article was written by Carrie Bennett and has been modified from it’s original version. You can find the original post here. Carrie is a facilitator, mediator, and trainer for Learning Through Difference, LLC. She loves helping groups get to the heart of issues that matter with safety and efficiency. Beyond work, she has a healthy obsession with backyard chickens, roller skates, and her freshwater shrimp Conrad. She lives in Northern Colorado with frequent visits to the Pacific Northwest.